The Noble Failure Of Esperanto

Translation services are vital in today’s world because products, services and information arew becoming more and more global. Japanese animation is voraciously consumed in America, French novels are read in Vietnam, and Australian mining companies offer their services to African clients. It requires a lot of effort and expertise to make sure that content is taken from its original language and accurately translated into many others for the world at large. It’s at times like this, especially for tourists and travelers, that many people wish there was one language that everyone spoke and understood. What many people don’t realize is that an attempt was actually once made to fill this need, and that language is called Esperanto.

A 19th Century Dream

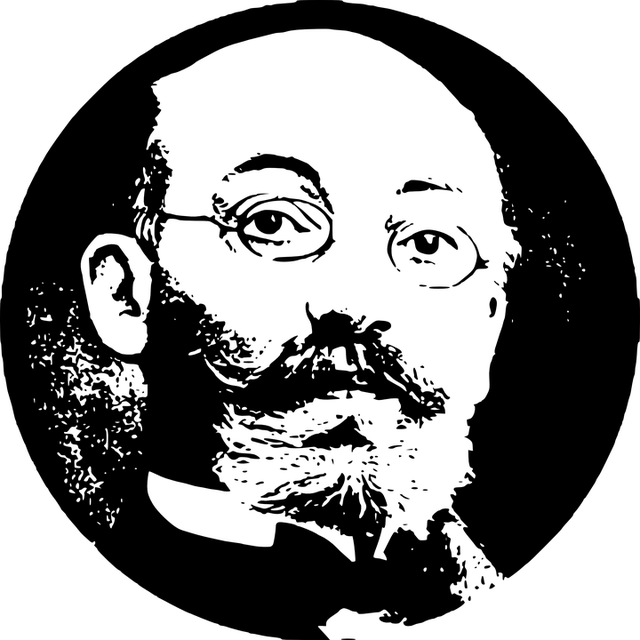

A Polish physician and linguist by the name of L. L. Zamenhof grew up in the city of Bialystok during the 19th century and saw a place divided by language. Jews, Germans, Poles and Russians were alienated from each other by language differences, and Zamenhof believed if they could all easily communicate with each other, fewer conflicts and misunderstandings would occur. In the 1880s, this led to his creation of Esperanto, an “artificial” language in the sense that unlike other languages that had naturally developed in various regions through trial, error and years of usage, Esperanto was made with one goal in mind; to be a language anyone could learn.

The biggest difference between Esperanto and other languages is that, unlike English, Esperanto has a basic system of easy to learn grammatical rules without the numerous exceptions that require memorization. Esperanto was intended to be a second language that speakers could use when not talking to natives of their region, and as such was made with a simple, sensible structure that some claim makes it four times easier to learn than any other language on the planet. Basic vocabulary and grammar is simple enough that even unfamiliar words can be deduced through the use of existing parts of vocabulary.

In many respects, Esperanto seems to offer everything in a language that people would want, so why isn’t it widely spoken?

Dreams Versus Reality

Esperanto is an easier language to learn for people in the West, thanks to its Eurocentric, Slavic roots, but is still problematic for Asian speakers who work under an entirely different set of language principles.

As a product of 19th century thinking, Esperanto occupies a strange place in linguistics. Esperanto is an easier language to learn for people in the West, thanks to its Eurocentric, Slavic roots, but is still problematic for Asian speakers who work under an entirely different set of language principles. There were also objections to learning it as a second language when it wasn’t already a wide-spread, liked useful business languages such as English or Chinese are today. Most parents prefer their children to learn the local, regional language for communication at home, while learning a widely spoken second language for career purposes. English is still much more widely used than Esperanto, which, as of 2013, still only has a few hundred thousand fluent speakers.

Despite this, there are Esperanto books, music and other content that is still produced every year for consumption. There is even an Esperanto World Congress held in different parts of the world for those people that do speak the language to come and share their interests. Esperanto may not have become the universal second language Zamenhof hoped for, but it has become an interesting cultural artifact for people still dreaming of a day when everyone understands everyone else.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!